|

| 1 | +# pycobytes[24] := *Alien **Kwargs |

| 2 | +<!-- #SQUARK live! |

| 3 | +| dest = issues/(issue)/24 |

| 4 | +| title = *Alien **Kwargs |

| 5 | +| head = *Alien **Kwargs |

| 6 | +| index = 24 |

| 7 | +| shard = syntax |

| 8 | +| date = 2025 April 4 |

| 9 | +--> |

| 10 | + |

| 11 | +> *Murphy’s law: whatever can go wrong, will go wrong*. |

| 12 | +

|

| 13 | +The `*` character does more than just multiply in Python. The alternate usage of it shows up in several places, often feeling like magic... |

| 14 | + |

| 15 | +```py |

| 16 | +>>> def func(*args): |

| 17 | + return [str(each) for each in args] |

| 18 | + |

| 19 | +>>> first, *rest = list(range(5)) |

| 20 | +>>> stuff = {*rest} |

| 21 | +>>> func(*stuff) |

| 22 | +["1", "2", "3", "4"] |

| 23 | +``` |

| 24 | + |

| 25 | +For me, there was a moment where it all “clicked” and it made perfect sense how `*` and `**` work. It can take time and experience to build this intuition, so in this issue, we’ll just have a look at how `*` is used specifically in function parameters. |

| 26 | + |

| 27 | +When we define functions, we can give them parameters that allow them to vary their behaviour. Let’s take a super-simple example of a function that finds the mean of 2 numbers: |

| 28 | + |

| 29 | +```py |

| 30 | +def average(x, y): |

| 31 | + return (x + y) / 2 |

| 32 | +``` |

| 33 | + |

| 34 | +When we call this function and pass in arguments, each argument is mapped to a corresponding parameter: |

| 35 | + |

| 36 | +```py |

| 37 | + # x is set to 1991 (first arg) |

| 38 | +>>> average(1991, 2025) |

| 39 | + # y is set to 2025 (second arg) |

| 40 | +2008 |

| 41 | +``` |

| 42 | + |

| 43 | +These are known as **positional arguments** – Python uses their *position* in the series of arguments to determine which parameter they’re meant to be. |

| 44 | + |

| 45 | +But we can also pass in the arguments by naming their corresponding parameter explicitly: |

| 46 | + |

| 47 | +```py |

| 48 | +>>> average(x = -1, y = 1) |

| 49 | +0 |

| 50 | +``` |

| 51 | + |

| 52 | +These are known as **keyword arguments** – probably since you’re identifying them via their parameter as a keyword. Interestingly, this means you don’t necessarily need to pass in the arguments in the exact order the parameters are listed: |

| 53 | + |

| 54 | +```py |

| 55 | +>>> average(y = 2, x = 5) |

| 56 | +3.5 |

| 57 | +``` |

| 58 | + |

| 59 | +Ok, so now let’s say we want our `average()` function to work with more numbers. We could hard-code it to take 3 numbers: |

| 60 | + |

| 61 | +```py |

| 62 | +def average(x, y, z): |

| 63 | + return (x + y + z) / 3 |

| 64 | +``` |

| 65 | + |

| 66 | +But now we can only pass in 3 numbers, not 2. Clearly things are getting out of hand. |

| 67 | + |

| 68 | +Sometimes what you need is a function that can take an arbitrary number of arguments. Something you could call like so: |

| 69 | + |

| 70 | +```py |

| 71 | +>>> echo() |

| 72 | +>>> echo("never") |

| 73 | +>>> echo("never", "gonna") |

| 74 | +>>> echo("never", "gonna", "give") |

| 75 | +>>> echo("never", "gonna", "give", "you") |

| 76 | +``` |

| 77 | + |

| 78 | +This is the magic of `*`. Put it before a parameter’s identifier, and that parameter will become arbitrary, absorbing all positional arguments into one `tuple`. |

| 79 | + |

| 80 | +```py |

| 81 | +>>> def test(*stuff) |

| 82 | + for each in stuff: |

| 83 | + print(each) |

| 84 | + |

| 85 | +>>> test("after", "prod") |

| 86 | +after |

| 87 | +prod |

| 88 | + |

| 89 | +>>> test(0, 0) |

| 90 | +0 |

| 91 | +0 |

| 92 | + |

| 93 | +>>> test() |

| 94 | +``` |

| 95 | + |

| 96 | +Hopefully this should work pretty intuitively. Where it can start to get confusing is when you *also* have positional parameters coming before: |

| 97 | + |

| 98 | +```py |

| 99 | +def mix(base, accent, *more): |

| 100 | + ... |

| 101 | +``` |

| 102 | + |

| 103 | +Here’s what happens when we call this function: |

| 104 | + |

| 105 | + - As many positional arguments are matched with positional parameters as possible (`base`, `accent`) |

| 106 | + - The remainder are ‘bundled’ into the arbitrary parameter (`*more`) |

| 107 | + |

| 108 | +Now you might look at this and think, “cool, but why wouldn’t you just use a single parameter which should be a list?” |

| 109 | + |

| 110 | +```py |

| 111 | +>>> def normalise(items: list[float]): |

| 112 | + ... |

| 113 | + |

| 114 | +>>> normalise([0.1, 0.7, -0.2, 1.3]) |

| 115 | +``` |

| 116 | + |

| 117 | +Well, this totally works, so it’s a difficult question to answer. |

| 118 | + |

| 119 | +As always, it depends on context. There’s rarely a technical reason why you would need `*args` over an `arg: list` – especially given how easily you can convert between them. What it does often do is make function calls a lot more ergonomic, and avoid bracketing nightmares. |

| 120 | + |

| 121 | +Fun fact, `print()` is defined with `*args`! This is why you can pass in multiple things, and they’ll all get printed out in sucession: |

| 122 | + |

| 123 | +```py |

| 124 | +>>> print("one") |

| 125 | +one |

| 126 | + |

| 127 | +>>> print("one", "two") |

| 128 | +one two |

| 129 | + |

| 130 | +>>> print("one", "two", "skip a few", "-1/12") |

| 131 | +one two skip a few -1/12 |

| 132 | +``` |

| 133 | + |

| 134 | +Can you imagine writing `print(["just one thing please"])`? bleugh. |

| 135 | + |

| 136 | + |

| 137 | +<br> |

| 138 | + |

| 139 | + |

| 140 | +--- |

| 141 | + |

| 142 | +<div align="center"> |

| 143 | + |

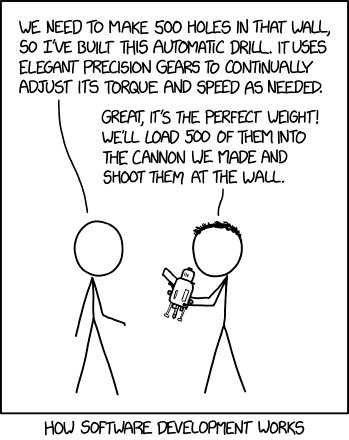

| 144 | +[](https://xkcd.com/2021) |

| 145 | + |

| 146 | +[*XKCD*, 2021](https://xkcd.com/2021) |

| 147 | + |

| 148 | +</div> |

0 commit comments